From a biological standpoint, being competitive played an important role for our evolution. Resources were scarce in terms of food, shelter and mating partners; therefore, individuals were forced to impose their superiority over others to ensure their fair share.

Competitiveness has remained hardwired in human nature having proved its utility for survival purposes. Competition can be found everywhere. Whether at the workplace, in a classroom or among friends we constantly seek to achieve a superior position relative to others.

In literature, competitive behavior has been extensively researched in the field of Economics and Psychology. As ever, a consensual definition of competitiveness across all scientific disciplines is still lacking and many questions remain unanswered.

Is competitiveness learned or are we born with it?

Are we competitive with all activities?

Why does competitiveness increase in certain settings?

Social comparison model of competition

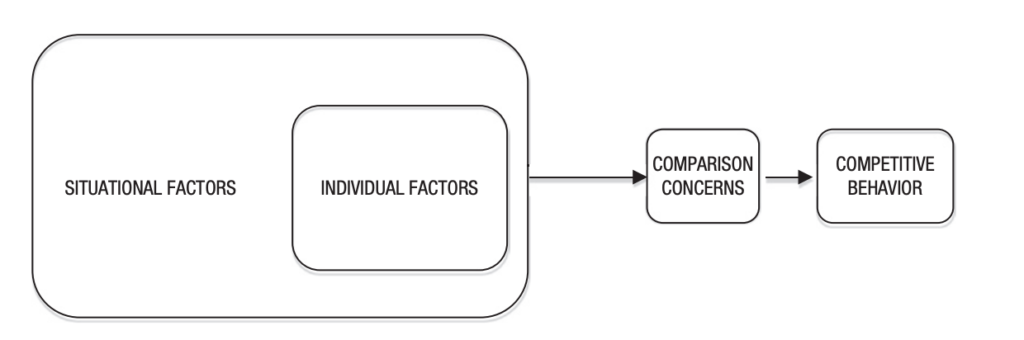

The Social Comparison Model of Competition (García, Tor & Schiff, 2013) provided its own answers to all these questions. The cornerstone of this model is the works of Leon Festinger, widely known due to his contribution to Social Psychology with his Cognitive Dissonance Theory.

In 1954 he went on to link social comparison processes to competitive behavior and posited that individuals are energized by an internal drive to outperform others to reduce discrepancies and, thusly, protect their superiority. Accordingly, “competitive behavior can be considered a manifestation of the social comparison process” (García et. al, 2013).

This desire to hold a superior position regarding others can be seen in both directions: upward towards those who are currently better performers and downward towards those who perform relatively worse but have the potential to improve their performance.

The Social Comparison Model of Comparison (see figure 1) intends to predict competitive behavior among individuals. Given the multi-determined nature of competitiveness, it’s only logical that the model considers the effect of situational factors alongside individual factors.

Individual factors

Personal factors

- Relevance of a performance dimension (sports, income or academics) for the actor. “People compete on dimensions that are relevant or important to the self.” (García et. al, 2013) What this means is that if I identify myself as a crossfitter, I’ll be more competitive about it.

- Individual differences: these include several factors that may increase one’s competitiveness:

- Social comparison orientation: personality trait defined as the tendency to compare oneself with others

- Competitive dispositions: a somewhat stable desire to participate and win in competitive settings

- Tendency towards performance goals (winning a tournament, ranking higher than others, etc.) rather than mastery goals (becoming highly proficient in a given task).

Relational factors

- Similarity to the target: when rivals are perceived as similar in performance levels they show greater comparison concerns. This is a stable in competitive sports: in soccer we have Messi vs. Cristiano Ronaldo, in tennis it’s Federer vs. Nadal and in CrossFit it’s Fraser vs. Froning.

- Closeness to the target: comparison concerns are stronger when the target is interpersonally close (friend, sibling, etc.) Research has shown that we are more threatened by our friends’ success than by that of strangers.

Situational factors

These are external factors that exist independently an exert a stable influence on the competitive behavior of the athlete.

- Incentive structures: these are inherent to competitive settings and include “Zero-sum” situations, for example, where victory for one athlete necessarily means defeat for another and raise athletes’ concerns about their relative position.

- Proximity to a standard: being crowned the “fittest on earth”, landing the podium… Furthermore, findings suggest that competitiveness is stronger near the top of the rankings compared to intermediately ranked athletes.

- Number of competitors: when the field of athletes decreases, concerns increase. This makes sense if we look at bracket-style tournaments for example where early stages are just preliminary steps towards the end goal which is reaching the final heat and winning the whole thing. As the field gets smaller, incentive goes up and, consequently, comparison concerns increase.

- Social category fault lines: defined as comparison against targets from other social categories. Comparing your performance to a foreign athlete would beget more competitive behavior than comparing to a fellow American.

Being competitive is not the recipe for success

The whole point of this article is basically a personal need to understand my own competitive nature and if it’s that important for performance. Many people describe themselves as competitive but I feel that this competitive disposition shows different manifestations and intensity levels depending on the athlete.

This disparity within the category of “competitive athletes” is even heavier among top-level athletes. All of them can be considered competitive and however the outcome is very different. For instance, Kara Saunders’ exhibited an insane degree of competitiveness in 2015 Murph where she ran the final mile under extreme heat exhaustion, remained in competition and managed to finish 5th overall. How can this level of competitiveness be paired to that of other athletes who are quick to throw in the towel?

I’ve always tried to find what mental aspect is the real deal for these athletes and it just can’t be something that’s found in every single one of them. Being competitive is not going to cut it when you reach the highest tier in sports. Nobody enjoys losing or coming in last so your competitive nature – however intense – doesn’t make you special.

Don’t admire Fraser for being competitive; praise his determination to not have a wheelhouse and constantly seek mastery in every physical skill. Don’t admire Tia Clair Toomey for winning back-to-back but praise her for overcoming self-doubt because that was a game-changer for her. It all comes down to what you’re willing to do to avoid losing and that has everything to do with motivation processes, coping methods and emotional management.