Cómo vencer a la falta de motivación para el cambio

No hace falta que dedique ningún tiempo a explicar los beneficios de un estilo de vida activo para prevenir enfermedades y mejorar nuestro estado psicológico y físico. Sin embargo, motivar un cambio hacia este estilo de vida (y mantenerlo) es tedioso. Es un camino lleno de obstáculos que ponen a prueba nuestra motivación y autoconfianza.

El objetivo de este artículo es el de profundizar en el proceso de cambio, desde no querer cambiar a decidirse repentinamente a darle un giro a nuestra vida y cómo podemos hacerlo con éxito.

Las Etapas del Cambio

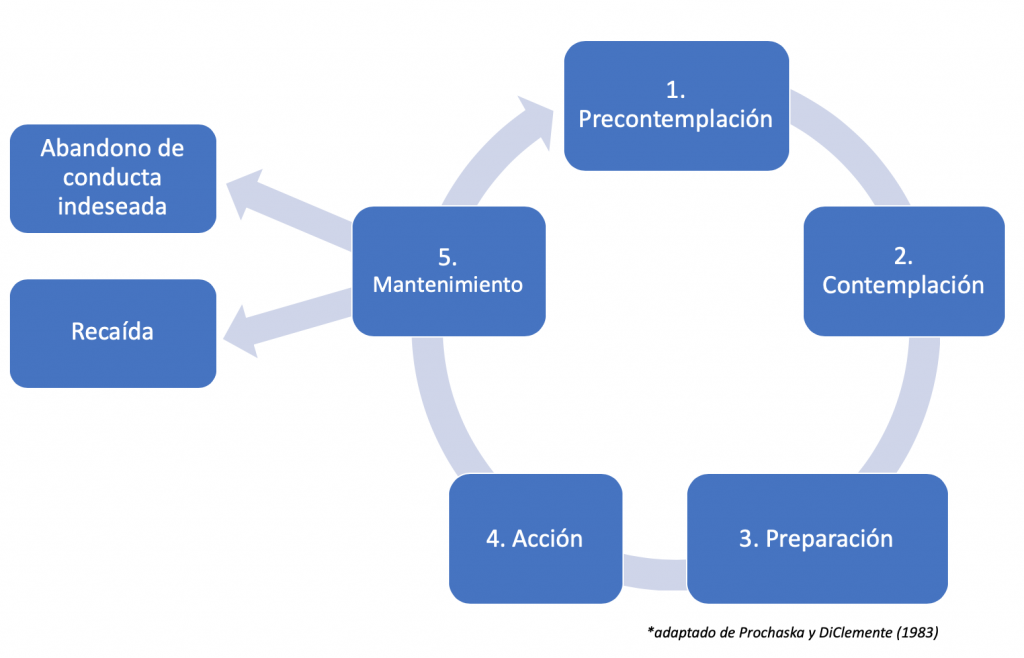

Este modelo empieza en un estado precontemplativo en que la persona no considera el cambio; después, pasa a la contemplación, y evalúa pros y contras de hacer ese cambio; entonces pasa a la preparación, donde se compromete a trazar un plan; desde ahí, pasa a la acción para empezar el cambio; y finalmente, la persona trabaja para un mantenimiento a largo plazo mientras lucha contra oportunidades de recaída (DiClemente y Velasquez, 2002).

Cuando a alguien le cuesta comprometerse con una rutina de ejercicio es porque viven entre la contemplación y la precontemplación (resulta que el modelo es cíclico con razón). Los precontempladores dirán cosas como: «No necesito entrenar, me siento genial así como estoy.»; mientras los contempladores dicen: «Pero me siento tan bien cuando entreno y echo de menos esa sensación.»

Para los propósitos de este artículo, me centraré en dar claves a los contempladores que están considerando cambiar hacia un estilo de vida activo y cómo pueden asegurar un compromiso real. Precontempladores… ya hablaremos en otro artículo.

El punto de partida

Veamos cómo se puede pasar de inapetencia a deseo por el cambio. Mat Fraser comentó que su primera experiencia con el fitness le llegó a los 12 años más o menos. Estaba jugando al fútbol y lanzó la pelota lejos y otro niño le llamó «culogordo» y lo mandó a por la pelota. Se sintió tan mal que decidió cambiar su dieta y empezar a entrenar en su garaje. Comía latas de atún, bolsas de espinaca y hacía flexiones, sit-ups y corría en la cinta.

Para él, el punto de partida fue un comentario de un compañero, pero esto puede precipitarse de mil maneras. Hay gente que decide cambiar a raíz de una condición médica y otros que ven un vídeo de CrossFit en YouTube y deciden cambiar radicalmente su vida en los años siguientes (esa fui yo).

Algo debe apretar el gatillo y llevarte a considerar la posibilidad real de cambio, creando una tensión interna entre lo que eres y lo que te gustaría ser para que te preguntes si lo que estás haciendo ahora realmente es lo que quieres.

Contemplación

Cuando empiezas a considerar el cambio, puedes pensar que ya has hecho la mitad del trabajo. Pero, naturalmente, nunca es tan fácil. Aunque estés activamente buscando información sobre los pros y las contras de cambiar tus hábitos (llegando incluso a convertirte en un experto en la materia), puedes sufrir lo que Prochaska y DiClemente (1998) llamaron «contemplación crónica».

Esto ocurre cuando encuentras que lo positivo y lo negativo asociado al cambio están equilibrados. Para cada ventaja encuentras un inconveniente y no terminas de desigualar la contienda. En este punto conviene acogerse al principio de cantidad y listar absolutamente todas las cosas que te vengan a la cabeza – por «absurdas» que puedan parecer -.

Llegará un momento en que algo sobresaldrá, ya sea ventaja o inconveniente, y te facilitará la toma de decisiones. En mi caso, cuando finalmente me planteé como objetivo llegar algún día a ser Rx en CrossFit, se desequilibró la balanza a favor del cambio. Estaba preparada para pasar de etapa.

Prepararse para el cambio

Cuando ya tienes la fuerza de voluntad, toca desarrollar un plan detallado que te ayude a obtener éxito. Este plan debe ser «aceptable, accesible y efectivo» (DiClemente y Velasquez, 2002). Has de anticipar posibles barreras (situaciones precipitantes, claves del entorno, etc.) y también potenciales fuentes de apoyo.

La razón de ser de este análisis realista de las dificultades que puedes encontrarte por el camino es la de tener preparados planes para cada contingencia. La ambivalencia entre aproximarse o evitar el cambio no termina durante esta etapa, de modo que debemos ser conscientes de que podemos salirnos del camino en cualquier momento.

«No es como que le das a pause y cuando tienes una recaída, le das al play y empiezas donde lo dejaste. Tu adicción está ahí fuera haciendo flexiones. Se está haciendo más fuerte.» – Mat Fraser

Hablando de cómo superó el alcoholismo en una entrevista.

Cómo se mantiene el cambio

Antes de nada, dejar claro que el mantenimiento lleva más de 21 días. Incluso tras 6 meses de acción puedes tener una recaída y volver al primer escalón. Entonces, ¿cómo mantenerse en el camino?

- La autoeficacia debe asumir el protagonismo

La variable que va a determinar el éxito en el proceso de cambio es la autoeficacia. Saberse capaz de completar una tarea te mantiene vivo frente a las dudas, situaciones de riesgo e incluso recaídas. Por eso es importante que tengas un rol activo en todo el proceso para que cada pequeña victoria lo cuentes como consecuencia directa de TUS acciones.

- La recaída es una posibilidad muy real

¡Sorpresa! No, no estás a salvo. ¿Cuántas veces ha pasado que alguien deja de fumar durante 10 años y, de repente, vuelve a caer? Cuando les preguntas, ni siquiera saben cómo pasó pero se dejan llevar desde ahí y parece que todos esos años limpio fueron en vano… ¿o lo fueron realmente?

Debes entender que aunque tu estés dispuesto a cambiar y preparado para actuar, tu entorno no tiene por qué hacerlo contigo. Quizá tu familia siga abusando de comidas ultraprocesadas o tus amigos sigan presionando para que salgas de fiesta. No vas a cortar hilos con tus amigos y tu familia, así que debes apoyarte en eso que mencioné antes (la autoeficacia, ¿recuerdas?).

- Pero si acabas cayendo…

Una de dos: o vuelves a la etapa de precontemplación o terminas alcanzando el deseado mantenimiento. La autoeficacia ataca de nuevo. Si la recaída te confirma esas dudas y autodiálogo negativo (¿ves como no podías conseguirlo?), entonces volverás al principito con 0 motivación para volver a empezar.

Sin embargo, si tu autoeficacia está trabajada y entiendes la recaída como un inconveniente temporal, podrás aprender de ello: ¿por qué ha pasado y cómo puedo prevenirlo? Reciclarás tu plan de acción y encontrarás soluciones personalizadas. Cuando empecé a cambiar mi nutrición, primero fue lo de contar macros; después, pasé a una dieta estricta de realfooding; y ahora, me he mantenido con una dieta vegana y ocasionalmente vegetariana, baja en ultraprocesados y no demasiado restrictiva (porque esto solía precipitar abandonos de la dieta).

Si hiciste los deberes cuando te preparabas para el cambio, quizá ya sepas por qué tuviste la recaída. Además (y quizá esto llegue de sorpresa), ¡no todo es una recaída! Sólo porque te saltaste la rutina un día, no significa que tengas que abandonar durante 3 meses. Si tu autoeficacia sigue fuerte, aparecerás al día siguiente listo para dar guerra. El cambio es una batalla diaria que se alimenta de cada pequeña decisión que tomamos en el día; asegúrate de que se quede con algo de hambre.

- DiClemente, C. C., y Velasquez, M. M. (2002). Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change, 2, 201-216 - Prochaska, James O., y Carlo C. DiClemente. "Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change." Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 51.3 (1983): 390.