How memory can improve your performance

Sounds like crazy talk, right? But the truth is that basic cognitive processes such as attention and memory are key to keeping the brain fit in high-tension moments as we saw in another article. Basically, when all is said and done the main perpetrator of our victories in sport and in life is our brain so we have to figure out how to help it improve your performance.

In this article I’ll be focusing on two basic notions regarding memory. I could say a whole lot about this process but I decided to focus on two due to their application to sport performance (I’ll talk more about it soon enough).

Why do we remember bad times better than the good times?

To answer this we need to go way back and revisit the adventures our hominid ancestors went through.

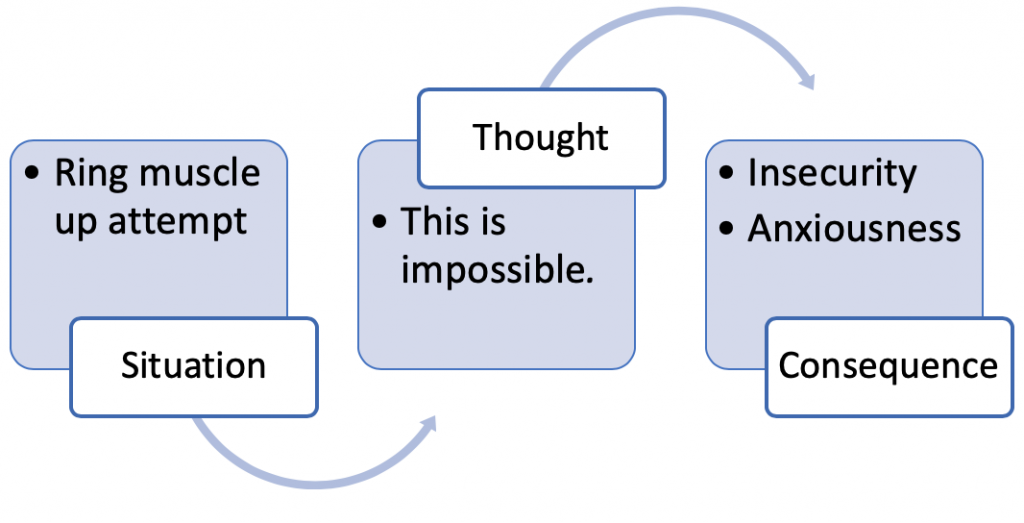

When a situation causes us a negative affective response, primary fight/flight actions are activated due to a basic instinct of pain avoidance. The first men faced wild animals and lived under adverse circumstance. The things they considered as aversive were truly life-threatening events. That’s why the brain started taking note of these situations quite seriously. Why? To anticipate and prepare adequate responses if any similar event showed up in the future.

Fast forward to the present day. Our negative situations don’t usually involve any risks to our physical well-being but our brain does its job anyways. The brain is still determined to pick up any little detail from the event and our response to it in order to provide enough information should they appear once more. So, it’s not our physical survival that’s endangered but our emotional survival.

Isn’t it funny that the very thing trying to save us from despair is the one that actually causes the pain? It’s like our brain is saying: hey, remember that thing that broke your heart? Yeah, well don’t you ever forget it (just in case).

Is our memory that reliable?

Those who believe their memory is flawless (guilty), couldn’t be further from the truth. There’s a very interesting TED talk on the matter that basically comes to prove that our memory is highly unreliable and changes day to day, from one person to the next, and that’s that.

Why is that so? Well, cause we’re not robots. We register information in a rather active fashion meaning we sugarcoat it with our own experiences, emotions, principles and values. Not only when we take it all in but also when it’s already stored; it starts to interact with other memory pathways causing even more confusion and disparity.

That’s why two individuals don’t remember the same situation the same way. Which makes for interesting and absurd arguments because, if memory is unreliable, how can we be so stubborn (or stupid) to assume we’re 100% right?

How can this improve your performance?

When it comes to our attachment to negative memories, I cannot stress enough how helpful it can actually be if you wish to improve your performance.

Not too long ago, Mat Fraser said he hated his silver medal from the 2015 CrossFit Games because he didn’t do things right and it costed him his first big W. However and to this day, he likes reminiscing about that outcome because it helped him detect his failures as an athlete and allowed him to «quit cutting corners». Ultimately, this transformed him into the 4x CrossFit Games champion we know now. Remembering something awful doesn’t need to be all that bad if we learn something from it.

Regarding memory’s so-called reliability… let’s reel it in and keep it humble. For many reasons. In competition and training even more so because we’re heavily influenced by our body’s activation so memory’s already biased.

A good example of how to do this the right why is Jeff Evans response to a gnarly no-rep at the 2016 Atlantic Regionals that kept him from getting back to the Games. Truth be told it was perfectly reasonable for Evans to lose his marbles and let out his fury against the judge, but that was not the case. He showed a top-notch emotional maturity by focusing only on previous execution errors in the weekend that had brought him to such a precarious situation going into the last event.

Any other athlete with poor emotional management would have sunk in the misery, going over and over the situation: the judge calling the no-rep, the feeling of devastation performing another rope climb knowing it didn’t matter anymore… but that was not the most adequate thing to do.

That’s why it’s so important to maintain a positive outlook on your memories so that you feel energized during the downfalls to improve your performance in the long run. Some athletes benefit from visualizing past mistakes to remember they don’t want to feel that way ever again; others may need to resort to past success stories. However it may be, memory can contribute to keeping the fire going but always with your two feet on the ground.