Cómo superar el miedo al fracaso en competición

Entre las muchas emociones elicitadas por entornos competitivos, el miedo al fracaso es el constructo que más atenciones ha recibido. En literatura, se ha conceptualizado como «una tendencia disposicional a experimentar aprehensión y ansiedad en situaciones de evaluación porque los individuos han aprendido que el fracaso está asociado a consecuencias aversivas» (Conroy y Elliot, 2004).

Una vez se definió el constructo, el siguiente paso era determinar la causalidad que explica su aparición y la naturaleza de su influencia sobre el comportamiento.

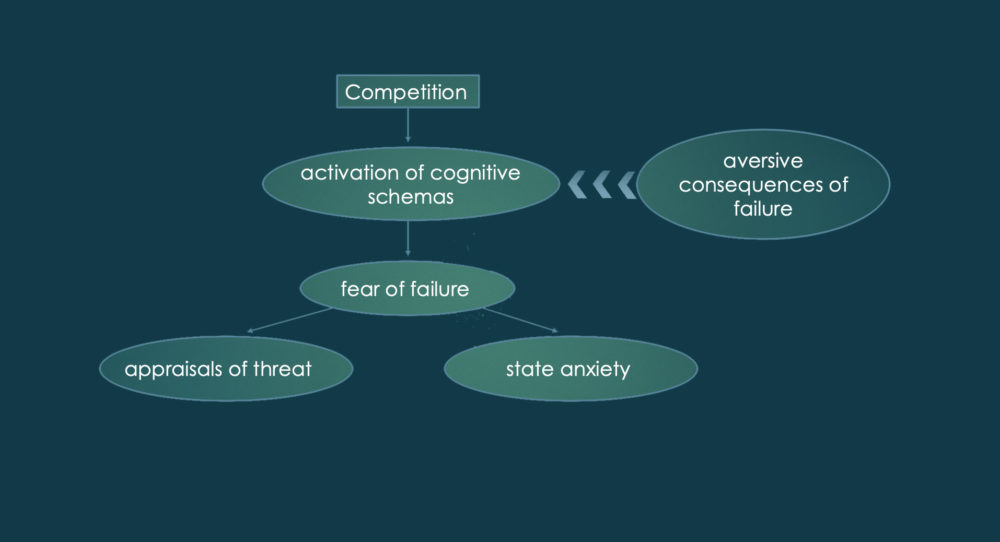

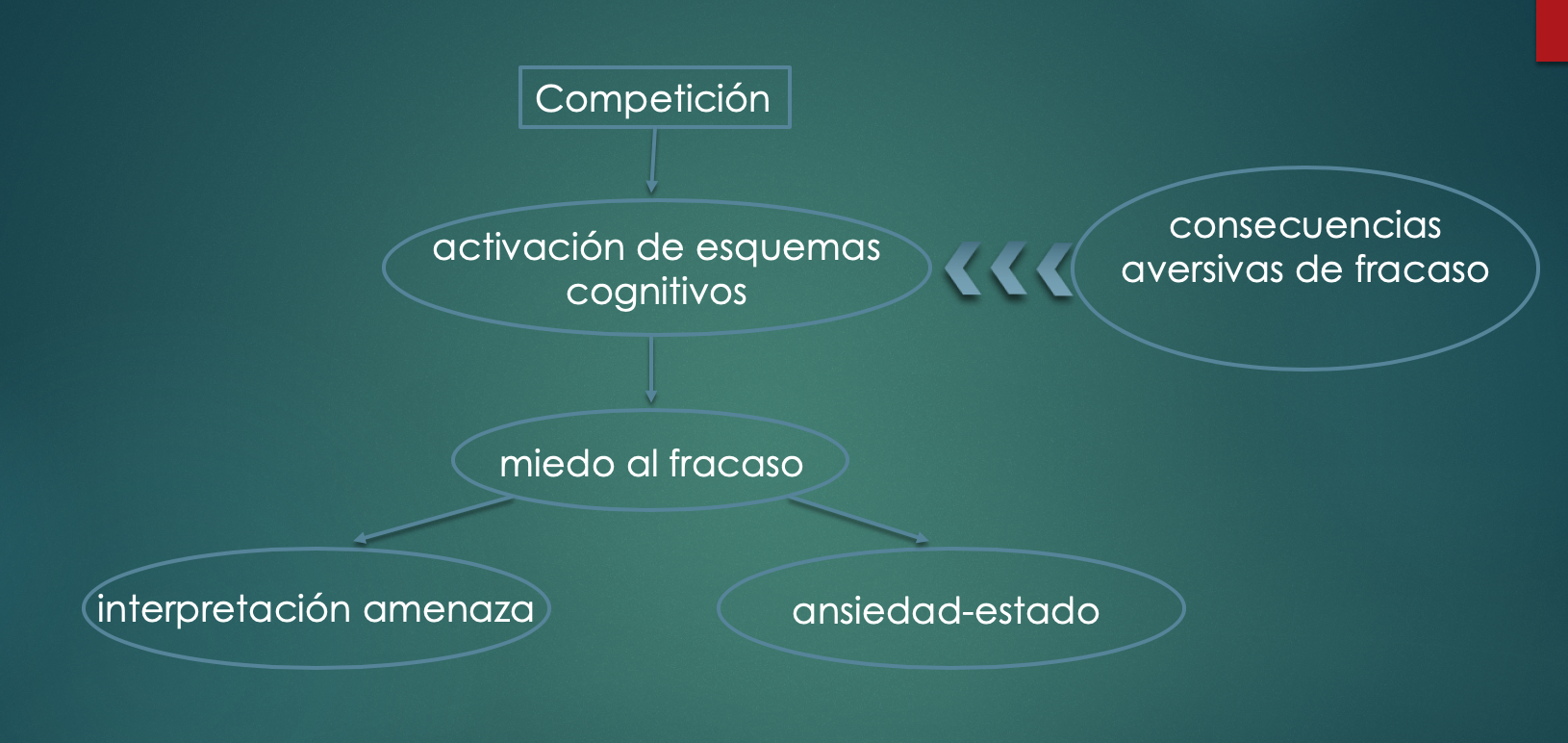

En lo que se refiere al proceso que genera este miedo al fracaso, existe un modelo jerárquico que postula que éste surge cuando el sujeto se enfrenta a una situación que supone alguna suerte de evaluación. Esta apreciación hace que el individuo active esquemas cognitivos sobre las consecuencias aversivas del fracaso que será lo que, en última instancia, genere ese miedo (Conroy y Elliot, 2004).

Las consecuencias de ese miedo difieren de unos a otros y – para variar – se reduce a las diferencias individuales. Entonces, ¿cómo manejo mi temor al fracaso cuando la exigencia es elevada? Sólo puedes aprender si te expones deliberadamente al error.

Hay razones para creer que esto es valioso para el rendimiento desde un punto de vista cognitivo y conductual. En el plano cognitivo, es fundamental que averigues cómo respondes a tus emociones, la naturaleza de tu autodiálogo y tus estrategias de afrontamiento. En un sentido más conductual, una exposición repetida conseguirá disminuir la intensidad de tu respuesta de miedo, facilitando la gestión emocional.

“Eres lo que haces”

Durante los años 60, hubo un fuerte interés hacia los aspectos conductuales que subyacen a la acción humana. El conductismo consideraba la conducta como algo completamente dependiente del refuerzo o el castigo que proporciona el entorno. Esta rama de la psicología nos aporta información muy valiosa como vimos en otro artículo.

En lo relativo al miedo al fracaso, también ha probado ser de utilidad. Conroy y Elliot (2004) consideraron el miedo al fracaso y la ansiedad rasgo de evaluación como “constructos conceptualmente equivalentes”, lo que me lleva a pensar que si la técnica de exposición funciona con la ansiedad, puede funcionar también con el miedo al fracaso (para más sobre esto, visita este artículo)

“Veo las cosas como soy, no como son”

En contraste, la Psicología Cognitiva irrumpió en la escena durante los 70 para llevarse consigo a mi corazón. Soy una fan empedernida de los aspectos cognitivos que dominan el comportamiento e, inevitablemente, recurro a estos factores cuando considero la causación de la conducta humana.

Para aprender a gestionar el temor al fracaso, podemos servirnos de la teoría cognitiva-motivacional-relacional desarrollada por Richard Lazarus, un autor de gran renombre dada su aportación al campo de las emociones. Esta teoría establece que la respuesta emocional actúa a tres niveles: experiencia subjetiva, acciones o impulsos para actuar; y cambios fisiológicos (Lazarus, 2000).

El marco de trabajo de Lazarus sentó las bases para que Conroy y Elliot desarrollaran el modelo jerárquico que consideraba el miedo al fracaso como un producto de los esquemas cognitivos que contenían consecuencias aversivas asociadas al fracaso (decepcionar a seres queridos, sentimientos de vergüenza, disminución de autoestima, perder el interés de seres queridos, etc.)

De ese modelo también se deriva la noción de que este temor al fallo estaba directamente relacionado con la ansiedad-rasgo de evaluación. Los individuos que generalmente temen cualquier forma de evaluación externa – situaciones en la que el comportamiento del sujeto se somete a juicio – tenderán a temer al fallo.

¿Cómo disminuir el miedo al fracaso?

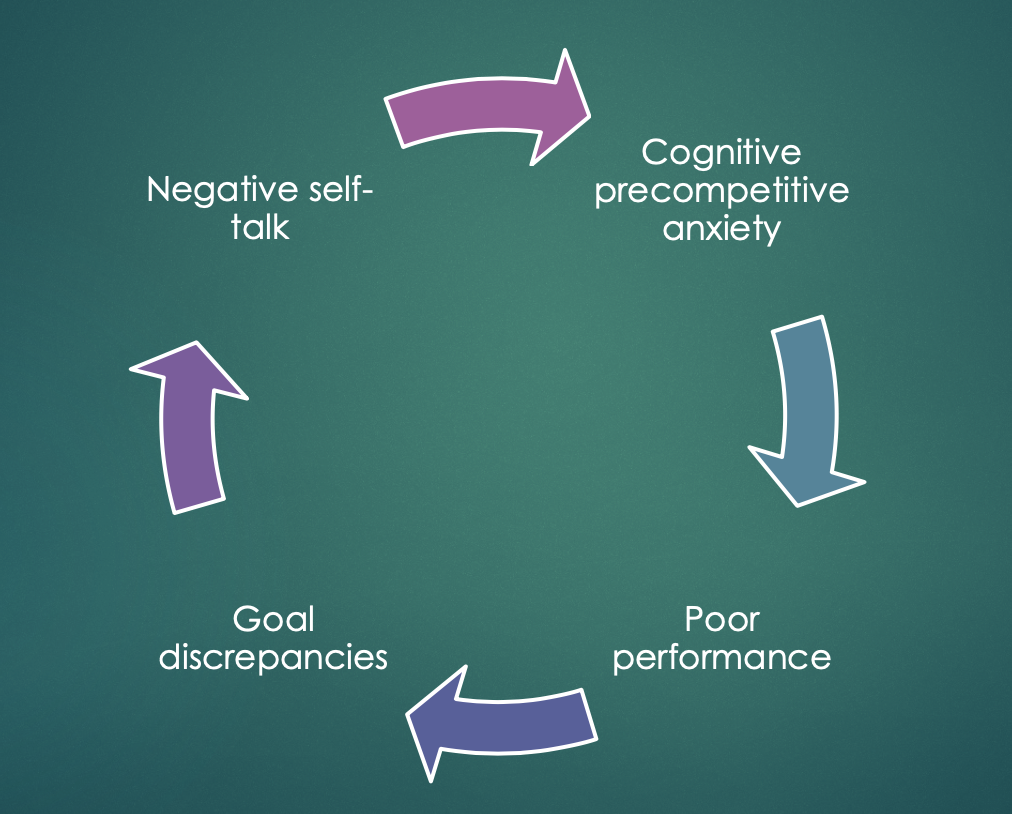

La consecuencia más grave de este temor al fracaso es que esa respuesta emocional afectará a tres procesos clave en el rendimiento deportivo: motivación, concentración y atención. Disminuirá nuestra motivación frente a la realización de la tarea y nuestra capacidad atencional y de concentración se ver

Como solución, Lazarus (2000) propone que los atletas dediquen tiempo a analizar las emociones que experimentan durante la competición así como la vulnerabilidad que representa para ellos y las estrategias de afrontamiento que emplean. ¿Por qué? Es sencillo. Una estrategia de afrontamiento eficiente durante una competición cuando las cosas no salen como uno planea, te permitirá “volver a motivarte y, por ende, ser capaz de atender y concentrarte de forma efectiva para mostrar tu nivel de excelencia” (Lazarus, 2000).

¿Qué mecanismos de afrontamiento son necesarios para blindarse frente a autodiálogo negativo? Eso es algo que sólo puede responderse desde dentro. Los competidores deben enfrentarse a situaciones en las que experimentan emociones negativas para practicar estrategias de afrontamiento (para más sobre el afrontamiento, visita este artículo) que les alejen de acciones contraproducentes que aparecen en respuesta a ese afecto negativo.

El fracaso es tan importante como el logro

Esto es sólo una recomendación general (no sólo aplicable al deporte). El fracaso juega un papel fundamental en la vida de todos y permanecerá por siempre. Muchas veces, el fracaso se asociará a una tarea que no es relevante para nuestras metas de realización pero habrá veces en que afecte a la forma en que nos percibimos a nosotros mismos y puede llevarnos a una crisis de identidad. Es importante que aprendamos a identificar y afrontar estas situaciones para seguir adelante sin perdernos en el proceso. No temas caerte…¡sino a no saber levantarte!

Conroy, D. E., & Elliot, A. J. (2004). Fear of failure and achievement goals in sport: Addressing the issue of the chicken and the egg. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 17(3), 271-285. Lazarus, R. S. (2000). How emotions influence performance in competitive sports. The sport psychologist, 14(3), 229-252.