Pre-competitive anxiety: friend or foe?

I’m guessing no one who’s ever found themselves in a competitive environment is a stranger to precompetitive anxiety. It’s a tale as old as time and it can hit you when you least expect it. Even when you’re just training at the gym. The coach starts that countdown and as the clock starts ticking, you feel your heart beating faster and faster as it approaches that final second and then…you’re off. For some, those first reps make anxiety settle into levels that allow for a significant improvement in performance. For others, however, anxiety stays too high as to where performance is hindered. How to find balance between the two ends of the continuum?

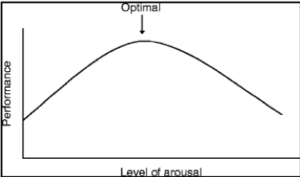

Aristotle said that virtue is the middle state between excess and deficiency and, unsurprisingly, this is applicable to precompetitive anxiety. This notion was scientifically demonstrated in 1908 by Yerkes and Dodson, two psychologists who found that there was a level of arousal – the physiological and psychological state of being “awoken” – that allowed optimal performance (figure 1). The ascending portion of the curve proves the positive effects of arousal, correlating with higher performance. Once the optimal point is surpassed, the negative effects of stress kick in and performance begins to decrease.

These negative effects take their toll on a cognitive, physiological and behavioral level. In the cognitive sense, you begin to overanalyze, lose ability to focus, are unable to make decisions and your mind is suddenly flooded with automatic negative thoughts. This process nurtures a sense of panic and fear that translates into an increase in heart rate and muscular tension. All this makes it complicated to follow through with the initial game plan so execution errors and ultimately a bad performance are the consequence.

What happens on the other side? Contrary to popular belief, those who are known to stay cold as ice prior to competing are not necessarily doing themselves a favor. Low levels of arousal are associated with lower body temperature, low motivation and decreased attention, amongst other aspects. Physically and mentally these symptoms are detrimental. A lower body temperature will difficult blood flow and muscle contraction. Decreased motivation and attentional levels will make it harder to produce high energy levels, affecting our concentration and focus. Try walking on your hands or snatching near your 1RM on pilot mode. Ain’t gonna happen. So, again, we’re messing up our performance without having even started.

«When I’m scared that I’m not capable in a workout (…) I really focus» – Mat Fraser

Mat Fraser, in my opinion, has seemed to crack the code on this one. He’s been on both ends of the continuum and it would appear he’s found his optimal arousal level given he’s been the unquestionable champion in the sport for the past 3 years. In relation to the 2016 CrossFit regionals he said in an interview: “When I’m scared that I’m not capable in a workout, you know, I really focus.” The reason he says this is because in Regional Nate he was terrified he would place extremely low in the event. He was unable to complete the workout inside the 20-minute time cap in training so he was sure it could be dangerous. Before starting that event, he was focused on one thing and one thing only: pushing through no matter what. He paid no mind to the excruciating pain in his upper body or his lungs and he ended up winning the event in the region, finishing the workout nearly a minute and a half within the time cap. However, other workouts where he felt more confident, he underperformed because he went into the event with a slight decrease in arousal levels, (i.e., not as scared and anxious). As soon as something started hurting a little, he would take a longer break, being passed by other athletes and before he could even react it was already too late to make a comeback. These experiences taught him a valuable lesson: fear fired up his performance.

As we’ve seen in science and CrossFit, anxiety plays a huge role in performance. But not all of us are exposed to high-stake competition the same way Mat Fraser is, so how can we know we’ve hit the sweet spot? Through practice and practice alone. We don’t need to sign up for every other competition for this goal; competition encompasses many areas. Trying to beat your training buddy or racing against a specific time cap can be enough. You can compete against a mental projection of Tia-Clair Toomey and imagine her picking up the bar every time you drop it; or include cash-outs with the worst combination of movements ever as punishment for not reaching the preset goal for a workout. Get creative! You need to experience difficulty just enough for you to fear not being able to make shit happen. This way, the fear component is present and it becomes relevant enough to elicit states of anxiety.

Once the workout is completed, record your performance and take note of any changes you noticed in your mental and physical state. If you’ve reached the goal for the workout, analyze the differences to increased your psychological awareness. Did you use positive or negative thinking? Maybe a mix of both. Did you change your strategy mid-workout or did you stick to the game plan? When your body started to give up on you, how did you manage to keep on moving? You need to figure out the behavioral pattern that relates best to higher performance. Naturally, this is subject to individual differences and optimal arousal level will change from one athlete to another. But if you learn how to panic in training, you’ll know just how much fear you need to perform to the best of your ability.