Overcoming fear in sports using behavioral modification

In sports there are many situations that can produce fear in the athlete and this emotional response can be elicited by diverse factors (personal, social, etc.). Consequently, we face an immense variety – as it so happens with anything that moves on a psychological plane – and this represents a great challenge if we seek to manage this fear in our athletes.

This fear can become an obstacle for our athlete’s learning process, rehabilitation program or overall athletic performance. That’s why we must find the most effective method to modulate the affective response. To do so, we’ll turn our attention to behavioral modification techniques, more specifically: systematic desensitization and prolonged exposure.

Systematic desensitization and prolonged exposure

During the 70s, cognitive-behavioral techniques experienced an exponential growth in psychotherapy. Therefore they were applied to different contexts, including sports. The goal was to enhance an optimal mental state in the athletes to improve their performance levels. Anxiety management techniques quickly became relevant to help overcome fear in sports.

In this sense, techniques such as the systematic desensitization (Wolpe, 1968) and prolonged exposure proved their worth. They’re both heavily influenced by Mowrer’s two-factor theory (1947) which explains the process of avoidance learning: fear is acquired by classic conditioning and maintained by means of avoidance and escape behaviors (Foa, 2011).

Main difference between both techniques is that SD includes a personalized hierarchy of feared situations and the individual faces each situation progressively using visualization and imagination. During prolonged exposures, on the other hand, individuals face the feared stimulus in real life.

Both techniques rely on two premises: extinction of the fear response (the initial response of the individual will tend to disappear after prolonged and repeated exposure to the stimulus), impeding escape or avoidance behaviors to facilitate extinction learning.

How does this apply to real-life situations

Summarizing these behavioral modification techniques in a few paragraphs might lead you to believe this is easy to perform in real-life settings… but you couldn’t be further from the truth. The reality is that this is quite complex and requires supervision from a specialized professional. The best way to help in the most extreme cases is to derive your athlete to a clinical psychologist.

However, there are some common guidelines that can be useful for everyday situations that may arise with our athletes (at any level of expertise). So I’ll detail those that may help overcome fear in sports.

Hierarchy of feared situations

The best way to understand this is using a real-life example: my mom! As many other women, she’s developed an irrational fear of doing box jumps. She’s physically capable of doing it but right when she’s about to lift her feet off the ground she stops in her tracks.

After several failed attempts, it was quite obvious that it wasn’t happening. So I askd myself: is there something else she might be willing to jump? Maybe 40 cm are too many and a 5-kg bumper plate seems more achievable. We progressively started piling up bumpers until we ran into that fear-avoidance pattern again.

So I shifted my focus and wondered if she’d be able to step up to the box or perform a jump alternating her feet. She wasn’t confident about jumping but she did manage to step up to the box (I stood there beside her just in case but she didn’t need me).

She started practicing 10-15 minutes after every session (repeated exposure) until one day she finally jumped. She alternated her feet but it was still an amazing achievement. Not only because it meant she was progressing in her athletic development but also because it boosted her self-confidence.

Impeding escape/avoidance

On paper, theory works wonders. However, there’s something we should be taking into consideration: who enjoys deliberately experiencing fear? As humans, we’re bound to two general principles that guide our behavior: approach pleasure and avoid pain. Therefore, we tend to escape from aversive situations. And this is exactly what we mustn’t allow.

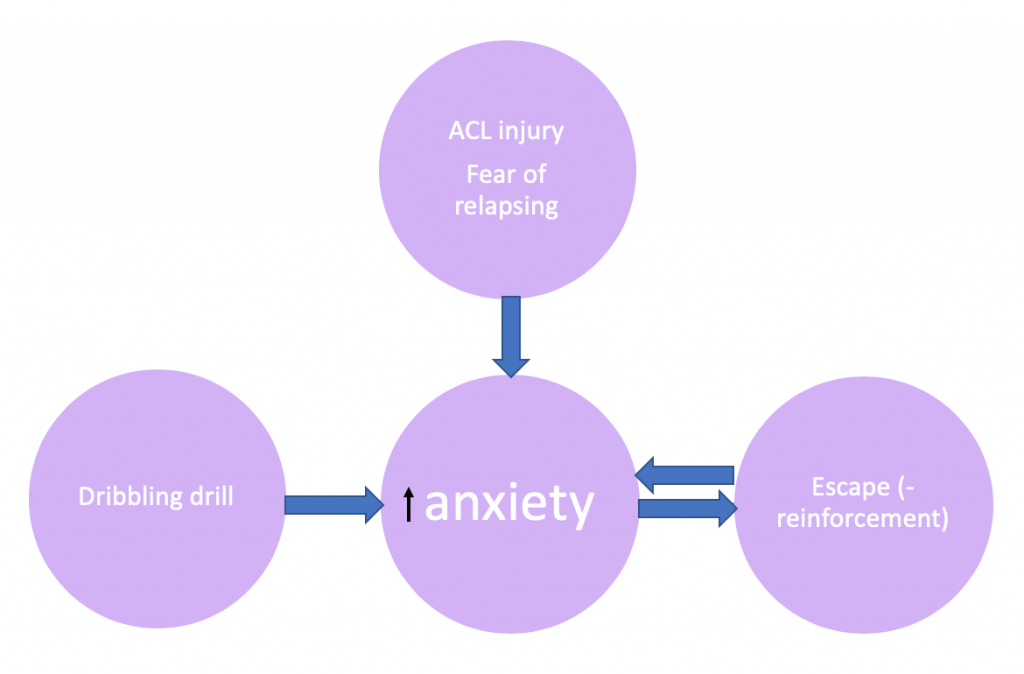

Let’s see how this “avoidance learning” works with another example. Here’s a soccer player who tore her ACL performing a change of direction and has been inactive for the last 8 months. When she’s allowed to begin her training again, she experiences fear when faced with drills that involve change of direction and she actively avoids them.

This is how it works (figure 1): when she must perform a dribbling exercise, she starts to experience anxious symptomatology because she tore her ACL changing direction and she’s scared of relapsing. Anxiety is so intense that she’s unable to complete the drill and skips it. Escaping the situation brings her anxiety levels down, acting as negative reinforcement (to learn more about this concept, read this post).

We’re trying to break this contingency through which changes of direction indicate the presence of danger (relapsing).

Our job is to “force” her to complete the exercise and re-evaluate the situation in a safe setting. Once she performs enough changes of direction without suffering any injuries, she’ll realize there was nothing to fear.

Recap

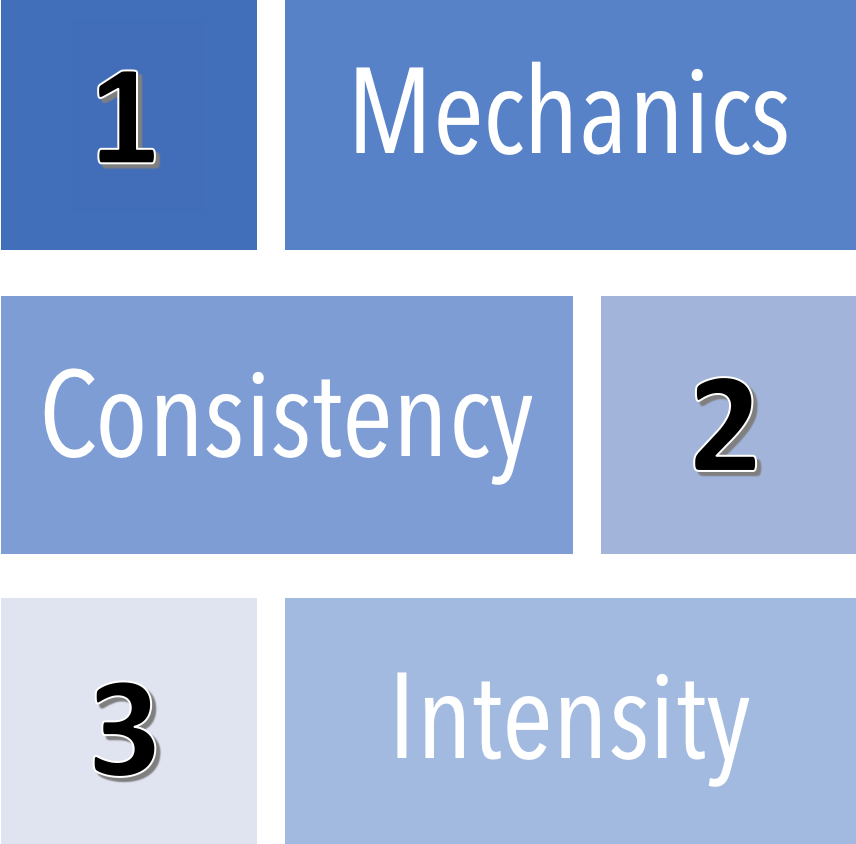

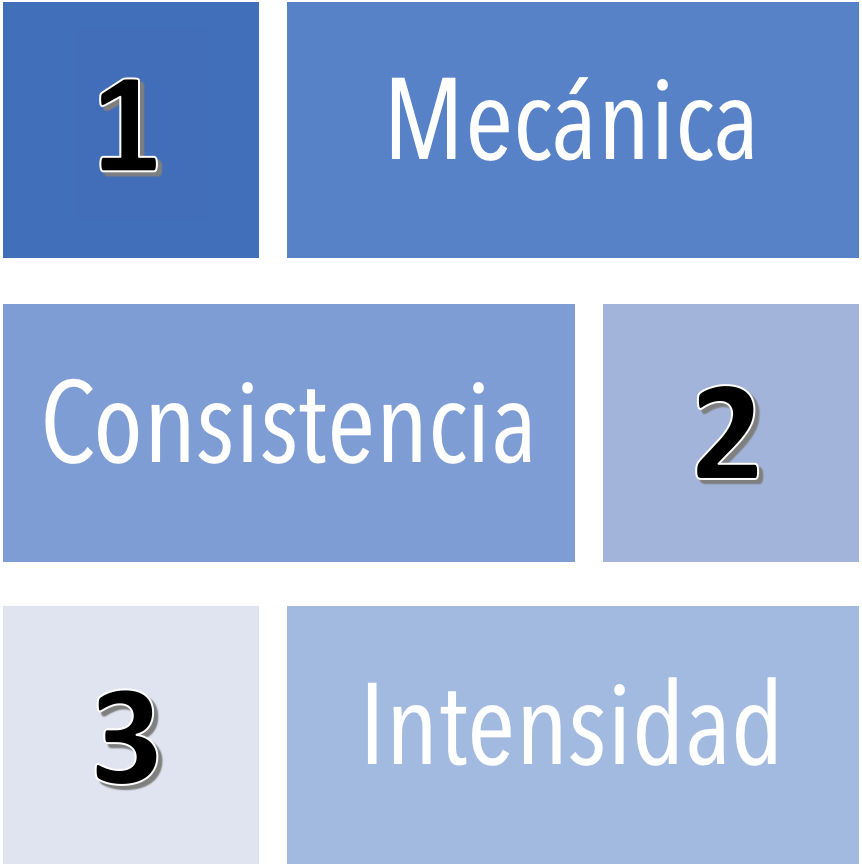

Fear in sports is a given so we must dedicate our efforts to finding the best way to manage this emotional response. In this article, I consider the possibility of using behavioral modification techniques which can be broken down into three key aspects:

- Listing fear situations according to their similarity to the original situation. This is especially helpful when anxiety levels are too high to expose the athlete from the get-go.

- Impeding escape/avoidance behaviors to break the contingency. They must learn that feared stimulus doesn’t predict danger or pain.

- Prolonged and repeated exposure to ensure full extinction of the conditioned response.

- Chirivella, Enrique Cantón. "La Psicología del Deporte como profesión especializada." Papeles del Psicólogo 31.3 (2010): 237-245.

- Ezquerro, M. (2008). Intervención psicológica en el deporte: revisión crítica y nuevas perspectivas. In V Congreso de la Asociación Española de Ciencias del Deporte. León.

- Foa, E. B. (2011). Prolonged exposure therapy: past, present, and future. Depression and anxiety.

- Mowrer, O. (1947). On the dual nature of learning—a re-interpretation of" conditioning" and" problem-solving.". Harvard educational review.

- Wolpe, J. (1968) Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Conditional Reflex 3,234–240