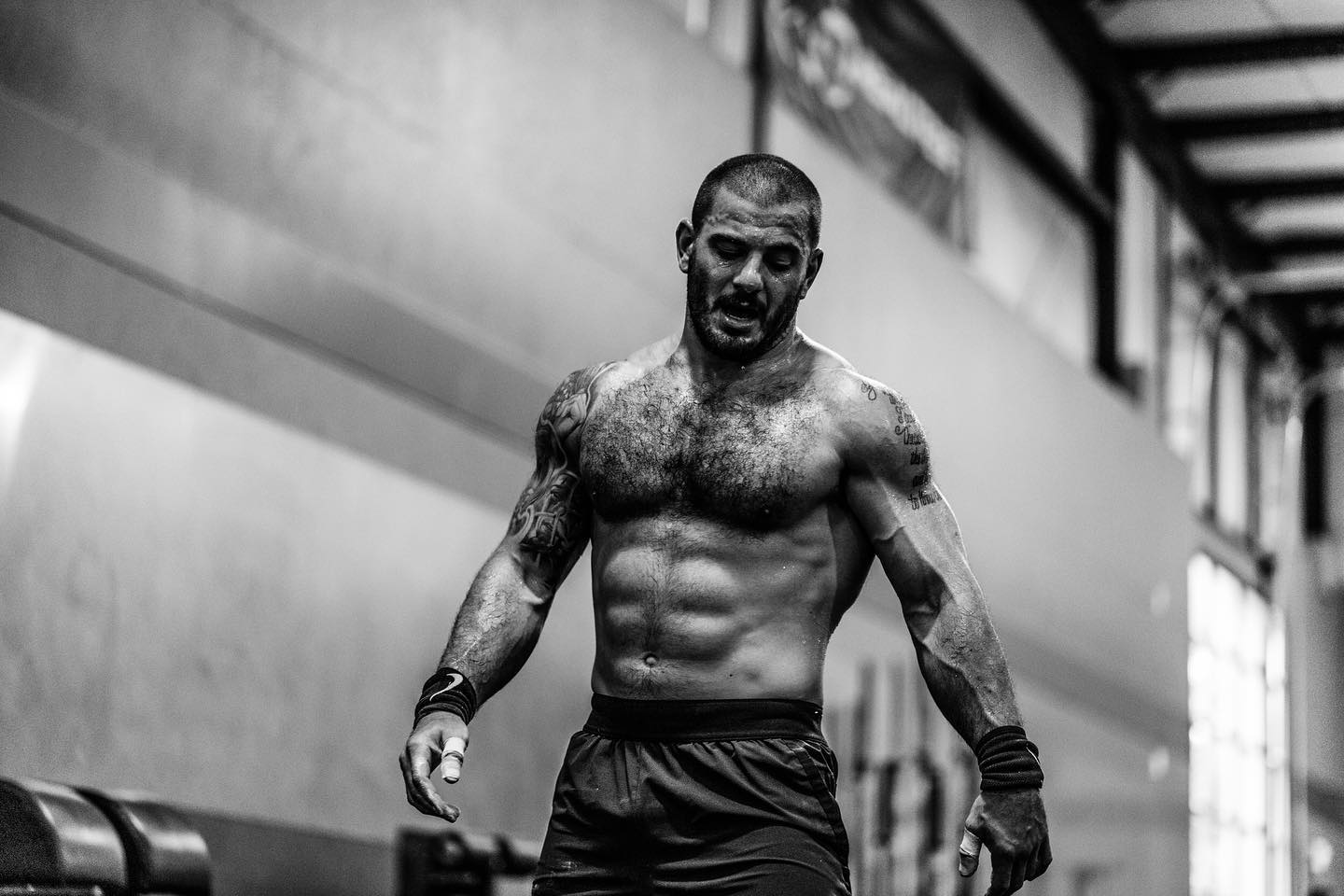

Mat Fraser and the psychological keys to his success

Mat Fraser is the most dominant athlete ever seen in the history of CrossFit. He has become the first athlete ever to become the «Fittest Man on Earth» 5 times in a row (2016-2020) and in such a dominant fashion that it’s silly at this point to think anyone can even try to take his throne.

After showing up on the scene at Regionals in 2013, he’s won 29 official CrossFit events (including the Open, Regionals, Sanctionals and the Games). His «worst showings» were a 7th place at Regionals in his first year and a 7th place in the Open in 2016.

At the 2016 CrossFit Games he beat second place Ben Smith with a 197 point spread, beating previous record set by Froning in 2012 (114-point lead). Fraser would go on to break his own record two times in a row in 2017 and 2018 with 216 and 220 points respectively. But wait, there’s more. In 2020 he broke his record (again) by crushing second place with a demolishing 545-point lead.

Where does his success come from?

Fitness aside (I’ll leave that to experts in Exercise Science), I can only consider the psychological components that may help explain his high-performance and consistency at the top of the «Sport of Fitness». That’s why I decided to write an article where I explain his keys to success from a psychological standpoint.

I’ve based the article on natural observation and information recollected from several interviews Fraser has given out in the past years. Therefore, these are by no chance scientific affirmations and they’re subject to my own personal interpretation as a professional psychologist.

– Intrinsic motivation

Intrinsic motivation, as we mentioned in another article, refers to participation in activities because of the pleasure or satisfaction derived from the activity itself. This condition is commonplace for the immense majority of high-level athletes who’ve achieved any success in their field.

Something that’s also very usual is the transition from an initial extrinsic motivation (guided by external consequences such as fame or money) towards an intrinsic motivation. This was the case with Fraser who claims he only started competing at local CrossFit competitions for the prize money.

After a while, motivation came from the personal satisfaction of going hard in training, continuously seeking progress as an athlete and solving problems daily. What makes him enjoy his days is knowing how hard he’s working to improve as a competitor and as a human being.

– Perceived control

One of the most salient aspects I’ve observed in Fraser during his CrossFit career is his perceived control. In several interviews he’s talked about identifying the situations he has control over to take action. For anything and everything that falls out of that condition, he practices acceptance.

Knowing when we have control over a certain situation is a common thread for many of the psychological skills that facilitate an optimal mental state. Fraser appears to have this particular skill locked down and this positively influences other cognitive processes:

- Coping – he’s faced some stressful life events (alcoholism at 17, losing his best friend, severe back injury that kept him away from weightlifting) and has learned how to pick his battles. He steps back, assesses his degree of control and acts accordingly.

- Decision-making – he’s simplified this process to its most basic form. For him, every situation offers two possible choices: one brings you closer to your goals and the other one keeps you further away. This allows him to keep his eyes on the prize and make every minor decision based on the greater goal.

– Anxiety management

Fraser has been pretty vocal about his intense pre-competitive anxiety. Before each event he vomits, dry heaves while this idea reverberates in his mind: «everyone is better than me». It’s mind-boggling that one of the most successful athletes in the sport carries the same fears as the rest of us regular mortals… but it’s in our nature.

The difference is that this pessimistic expectation – which is out of his hands – makes him re-evaluate the things he does have control over: his effort and execution in the event. In a certain way, thinking he’s already lost relieves some of the pressure, allowing him to focus all his energy on his own execution and the pain he’s willing to endure to perform at the highest level.

Turns out that from a psychophysiological point of view, anxiety can be positive and actually enhance performance (for more information on this matter, check out this article).

– Problem-solving

Any deficit in our fitness is a problem, right? To fix it we usually have to implement all sorts of actions; and Mat Fraser has proven to be a master at fixing weaknesses. How else would he have gone from sucking so bad at cardio back in 2013 to winning the 7k trail run in 2016 (among other examples)? But… how does he do it?

His method was born thanks to a Thermodynamics teacher he had at college. Fraser says he «learned how to learn». He never understood a word during the teacher’s lecture so he developed a habit: reading the chapter, taking note of any concept he didn’t understand, look for information on these concepts until he fully comprehended them and then read the chapter again.

This method was then applied to CrossFit. Generally speaking, it’s a very intuitive strategy that we all follow at some point; but the details make a big difference, what he calls «1% advantages». He trusts that all these 1% advantages will bring him closer to the end goal. Meanwhile, the rest of us tend to slack off or half-ass it when we work on our faults.

- Weakness identification

Fraser is very meticulous in his observations and has a special ability to narrow in on his weaknesses. Also, he doesn’t rest on his laurels for a second; he looks for execution errors even in the events he’s won. For example, during the Suicide Sprint in 2016 he realized Ben Smith got ahead after coming out of each pylon; meaning his acceleration wasn’t up to par yet.

Once he identifies a hole in his fitness, he breaks it down into a thousand smaller more manageable steps. Then he proceeds to the next step: tackling them one by one.

2. Pounding weaknesses into strengths

Mat Fraser has an undying desire to progress as an athlete. Wanting to become the best in every physical challenge he’s presented with sounds like madness; but that’s precisely the kind of ambition that allows him to stay two steps ahead of everybody else.

This inner fire is kept alive by polarized thinking. His famous «second place sucks» belief, or his dislike for goals that allow opinion; or his suicide pace on the last event of the Games in 2019, risking it all for that gold medal…lead to believe that Fraser lives by and «all or nothing» code.

When he works on his weaknesses, he stays true to that same code:

- After 2013 Regionals he bought himself a rower because he did terrible on the rowing portion of Jackie. He spent the better part of the following year rowing 5 km a day.

- In 2016, after crashing and burning in the sprint event and the Soccer Chipper with the Pig, he spent the year training twice a week with 14-year old track athletes to improve his sprinting technique and he also bought a Pig to flip it and flip it for days on end.

And these are but a few examples he’s been kind enough to share with the general public. I’m pretty sure that’s how he’s worked on each and every one of his physical skills.

Will it work for me too?

Probably not. Especially if you try to follow it word by word. Fraser has learned to take advantage of his personal traits so he doesn’t have to depend solely on his supernatural athleticism; but there is no universal formula for success. We all need to find the right ingredients for our own recipe.

However, getting some ideas here and there is a good place to start. Truth is, Fraser’s repertoire is filled with many tools we may find useful.