Cómo trabajar el miedo en el deporte

En el deporte se dan numerosas situaciones que pueden producir miedo y ésta puede ser elicitada por una gran diversidad de factores (personales, sociales, etc.). Por ello, nos encontramos ante una gran variabilidad – como ocurre con todo lo que se mueve en el plano psicológico – y eso dificulta su gestión.

Este miedo puede obstaculizar el aprendizaje de un atleta, su rendimiento competitivo, su readaptación tras una lesión,… y, es por ello, que debemos descubrir el modo más eficaz de moderar esta respuesta afectiva. Para ello, vamos a volver a poner el foco en técnicas conductuales: en este caso, la desensibilización sistemática y la exposición prolongada.

¿Puedo manejar el miedo en el deporte?

La respuesta es sí, y la metodología suele incluir técnicas cognitivo-conductuales. Dichas técnicas se fueron introduciendo al ámbito del deporte para ayudar a los atletas a alcanzar un estado mental óptimo. Más específicamente, se emplean técnicas de gestión de la ansiedad para trabajar el miedo en el deporte.

Y es aquí donde uno encuentra la utilidad de técnicas conductuales como la desensibilización sistemática de Wolpe y la exposición. La principal diferencia entre ambas es que en la DS el individuo se va exponiendo a sus miedos progresivamente a través de la imaginación; la exposición, por otra parte, se realiza en vivo.

Ambas técnicas buscan la extinción de la respuesta de miedo (que es la desaparición de una respuesta a un estímulo tras exposiciones prolongadas y/o repetidas), impidiendo conductas de escape y evitación.

¿Cómo se aplican estas técnicas?

Resumir estas técnicas conductuales en tres párrafos puede hacer pensar que su aplicación en un contexto real es pan comido… y nada más lejos de la realidad. De hecho, en casos muy extremos donde la ansiedad experimentada por el atleta le provoque un malestar significativo, lo más recomendable es derivar a un terapeuta especializado en psicología clínica.

Por eso – y para evitar desdibujar la línea que separa a un entrenador de un psicólogo – voy a detallar dos generalidades de ambas técnicas para su uso en situaciones específicas que puedan darse con nuestros atletas.

-

Jerarquizar situaciones temidas

La mejor forma de entender esto es con un ejemplo y, para ello, vamos a basarnos en una experiencia real: ¡la de mi madre! Ella, como otras muchas mujeres, tiene miedo a saltar al cajón. Tiene la capacidad física para hacerlo pero justo cuando debe dar el salto se frena y huye despavorida.

Tras varios intentos fallidos resultó obvio que no iba a pasar, así que me pregunté si habría alguna otra cosa que sí estuviera dispuesta a saltar. Quizá 40 centímetros eran muchos, pero a lo mejor un disco de 5 kg le resultaba más asequible. A partir de ahí empezamos a sumar altura de disco en disco hasta que volvimos a encontrarnos con esa secuencia de miedo-evitación.

Entonces cambiamos el foco y me pregunté si se veía capaz de subir al cajón con un «step-up» o si podría hacer un salto alternando pies (en lugar de saltar con los pies juntos). El salto no iba a ocurrir, pero el «step-up» sí que fue posible (teniéndome a mí como salvavidas al lado del cajón, aunque no fui necesaria).

Empezó a dedicarle los últimos minutos de cada sesión en el box a practicar el salto (exposiciones repetidas) hasta que un día me sorprendió saltando al cajón. Lo hizo alternando los pies pero ése fue un paso muy grande que, además de suponer un avance en su capacidad física, también tuvo una consecuencia muy positiva para su autoconfianza.

-

Impedir el escape o la evitación del atleta

Sobre el papel, la teoría funciona de maravilla. Sin embargo, existe un contratiempo: ¿a quién le gusta exponerse deliberadamente a algo que teme? Como humanos, nuestra conducta se rige por dos principios básicos: aproxímate al placer y evita el daño. Por tanto, tendemos a evitar situaciones aversivas. Y es precisamente lo que tenemos que impedir.

Veamos cómo se forma esta contingencia con otro caso hipotético. Tenemos a un futbolista que se rompió el ligamento cruzado anterior haciendo un cambio de dirección y lleva parado 8 meses. Cuando recibe el alta deportiva y vuelve para su programa de readaptación, muestra miedo a los ejercicios que implican cambios de dirección y los evita.

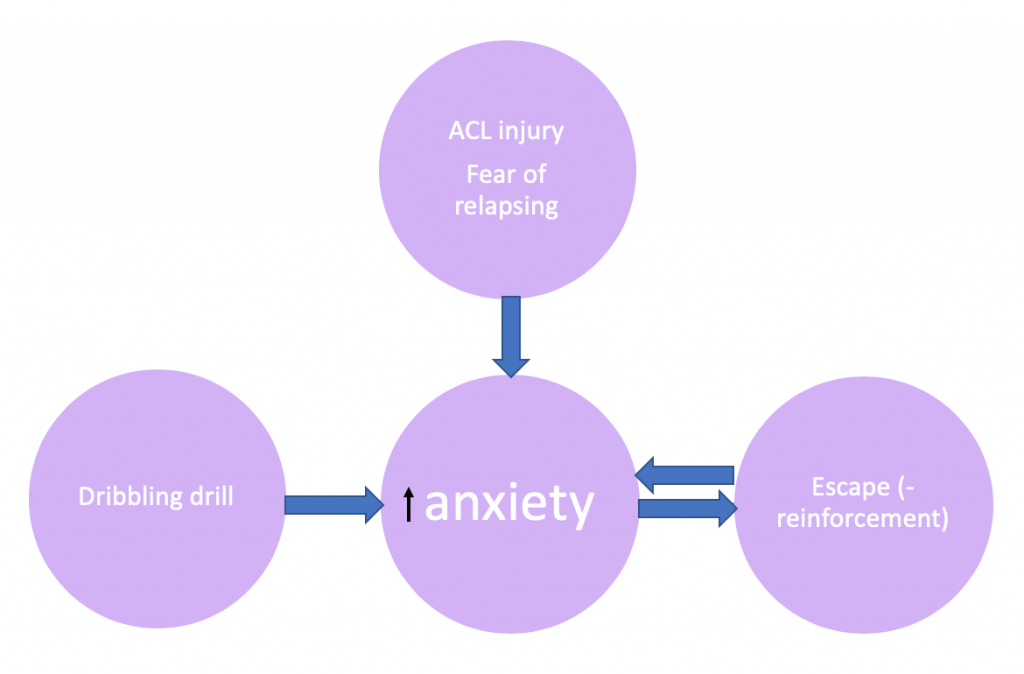

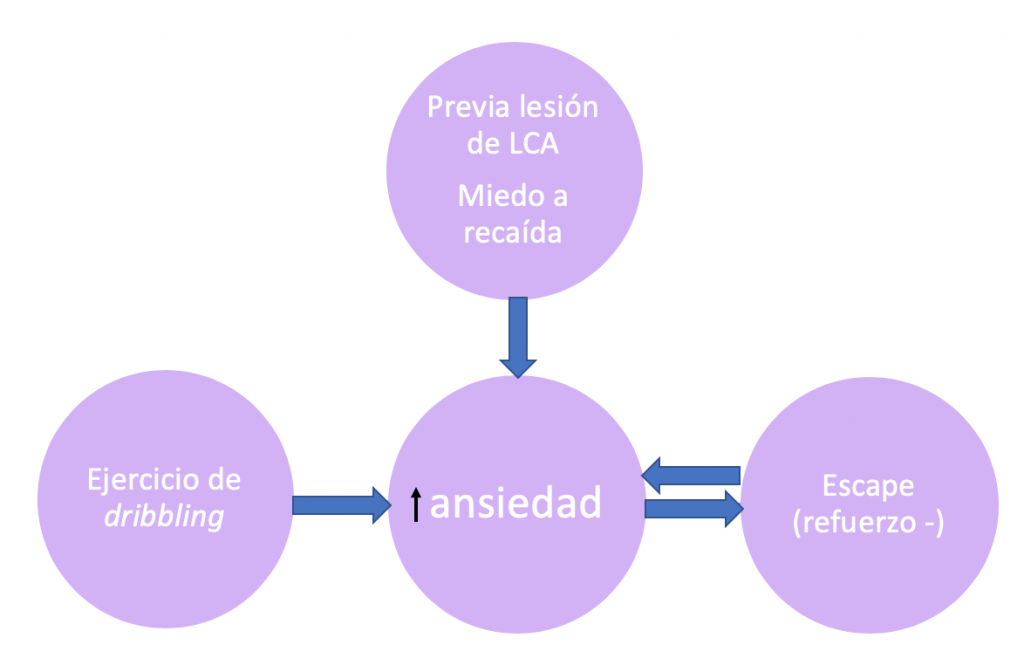

Cuando al futbolista se le plantea un ejercicio de dribbling con el balón (ver figura 1), éste empieza a experimentar síntomas de ansiedad porque su lesión se produjo en un cambio de dirección y teme sufrir una recaída. La ansiedad alcanza tal intensidad que el futbolista no es capaz de hacerlo y pasa a otro ejercicio. Escapar de la situación hace que su ansiedad desaparezca, lo que actúa como refuerzo negativo (para ver más sobre este concepto, mira este artículo).

Queremos romper esa contingencia y que la ansiedad no obstaculice la realización del ejercicio.

Nuestro trabajo será impedir que el futbolista huya de la situación y aprenda que el cambio de dirección ya no predice un peligro inminente (lesionarse).

En resumen…

El miedo en el deporte será una constante y debemos encontrar el mejor modo de gestionar esa respuesta en el deportista. En este artículo os planteo la posibilidad de basarnos en los principios de la modificación de conducta para este propósito y aquí os resumo sus claves.

- Listar las situaciones temidas según mayor o menor aproximación a la situación original. Esto nos permite trabajar en aquellos casos en los que la intensidad de la respuesta de ansiedad sea demasiado elevada.

- Impedir conductas de escape o evitación para romper la contingencia. Deben re-aprender que el estímulo temido no representa un peligro.

- Exposiciones prolongadas y repetidas para asegurarnos de que se produce la extinción del miedo.

¿Necesitas ayuda para superar tus miedos en el deporte? ¡Contáctame!

- Chirivella, Enrique Cantón. "La Psicología del Deporte como profesión especializada." Papeles del Psicólogo 31.3 (2010): 237-245. - Ezquerro, M. (2008). Intervención psicológica en el deporte: revisión crítica y nuevas perspectivas. In V Congreso de la Asociación Española de Ciencias del Deporte. León. - Foa, E. B. (2011). Prolonged exposure therapy: past, present, and future. Depression and anxiety. - Mowrer, O. (1947). On the dual nature of learning—a re-interpretation of" conditioning" and" problem-solving.". Harvard educational review. - Wolpe, J. (1968) Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Conditional Reflex 3, 234–240