Dealing with emotions

Emotions are an inextricable part of life. All life events would pretty much lose their power if they were emotionally detached. It seems, also, that emotion has a great influence on our behavior when responding to these life events (Smith & Lazarus, 1990).

Emotion comes from latin word emovere which means something like external movement. So we could say that emotion is a force that moves us to behaving in a certain way.

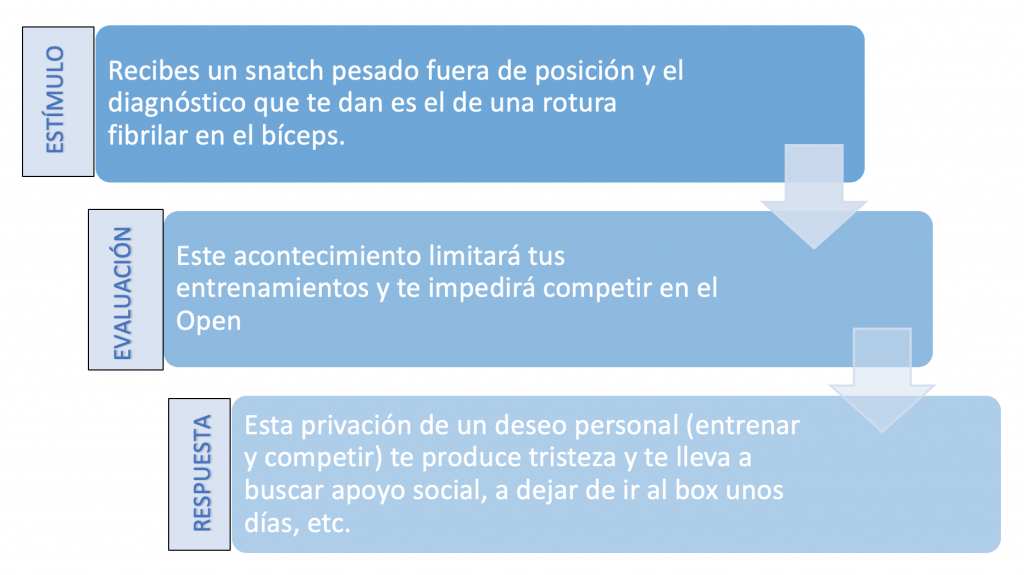

What we also know is that emotion follows a sequential process (Gross & Thompson, 2007): we perceive a stimulus, we appraise this stimulus and we respond to it.

Example: You receive a snatch out of position causing you to tear your bicep (stimulus). This injury will limit you in training and you won’t be able to compete in the Open (appraisal). You’ll be deprived of completing these goals which will make you sad and have you look for support in friends and family, quit going to the gym for a few day, etc. (response).

Don’t you love lists? They make everything so much easier but the truth is that there’s more than meets the eye when it comes to emotional processing. Especially considering that intermediate step: appraisal.

Theory of emotions

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) came up with a Appraisal Theory which was subdivided into two processes:

- Primary appraisal: we look for answers to the question «does this affect me personally?» To answer this question we consider the potential impact an event has on our personal goals and concerns (motivational relevance). Then, we proceed to evaluate how this event impedes or facilitates reaching our goals (motivational congruence).

- Secondary appraisal: this allows us to determine our control over the event, if I can change it or improve it according to my personal interest. We ponder 4 dimensions:

- Accountability: it’s not as simple as picking someone to blame. We take into consideration the intentions of whoever harmed us. If we think their actions were just, un-intentioned or inevitable, we won’t hold them accountable for our emotional reaction.

- Potential emotion-focused coping strategies: potential ability to readjust our emotional reaction into a more adaptative affective state that doesn’t interfere with out wellbeing in a significant way.

- Potential problem-focused coping strategies: what can I do to extinguish the source of the problem or alleviate its consequences.

- Future expectancy: which changes can occur for me on a psychological level to consider this life event as facilitating for reaching my goals.

Let’s see all this with an example from real life (my life).

I had a friend of mine record 16.1 Open workout for me and after 20 tough minutes, I found out my friend shut down the camera by mistake in the middle of it and didn’t dare tell me about it until the end.

Primary appraisal

Motivational relevance: my goal was to complete my first Open and load the scores onto the leaderboard. Back in 2016 I was affiliated in a box that had no judges to validate your scores so all I could do was load the video on YouTube. Verdict: yes, this affects my personal goals.

Motivational congruence: my first attempt going up in flames due to technical difficulties made it impossible to load that score onto the leaderboard.

Secondary appraisal

Accountability: technically my friend was to blame for the whole situation but it was completely un-intentioned. Known for being a bit clumsy but with the biggest Universe, I knew she would take it back if she could… and that’s why I couldn’t be mad at her. My emotions were a reaction to the situation, not to her wrong-doing.

Potential problem-focused coping strategies: the video had to be filmed from wire to wire, otherwise it wouldn’t count. So all I could do to fix it was re-do it.

Potential emotion-focused coping strategies: it’s obviously messed up to have to go through 20 minutes of lunges, burpees and pull-ups but I had plenty of days to re-do it and meet the deadline.

Future expectancy: in a second attempt I could try reducing transition times, breaking up the pull-ups… maybe I’d even get a better score than the first go-round (it wasn’t the case).

All this probably helped me deal with the situation in a way that didn’t harm my relationship with my friend or with the rest of the Open. I could have just gone crazy and threw the biggest fit ever, leading me to argue and badmouth my friend, blame that

situation for my poor results in 16.1 and just lose my mind. But I didn’t. Hence the importance of proper emotional regulation.

Applying this to the sport of Fitness

Is this even real life? It’s a legit question because it seems rather cost-worthy to go through all that processing for every life event. Every author comes up with their models and love to think that’s the real deal right there. But the truth is we’re still talking about something inmaterial as is human behavior.

I chose this model because it’s proven to be useful to train regulation of your emotions. Although you don’t see it through to the very end (it’s a pretty long exercise) it allows us to reflect upon the impact certain events may have in our day-to-day life and help us manage our consequential behavior. Sports ridden with success and failure stories so we must learn to modulate our emotional response to these.

No, it’s not about suppressing your emotions. There’s times to where you’re allowed to feel angry, afraid, sad… thing is: use that emotion in a conscientious and adaptive manner. If you’re gonna wreck it all, run away from life and hide in a cave, that’s bad business. If you’re sad due to something that’s out of anyone’s control, re-write the way you look at it.

Froning’s epic fail in the 2010 CrossFit Games helped him find deeper and more powerful motivation. Tia-Clair Toomey‘s success in 2017 gave her reason to believe she could trust her ability as an top-notch athlete. Your emotional state gives you valuable information; use your emotions to learn more about yourself as both an athlete and a person. Don’t forget emotions are the consequence of thousands of years of evolution. It’s a biological gift we must learn to use.