The dos and don’ts of inner dialogue

How many thoughts do we produce on a daily basis? 100? 300,000? The number 70,000 has been roaming around the scene for a while but it can’t be scientifically proven due to the experimental challenges that arise. How can you measure something as intangible and generally inaccessible as human thought?

Self-talk generates a million unanswered questions. What we do know is that we think a lot. Whatever we are doing at any point in time is generally accompanied by some form of private monologue that may or may not have to do with the task at hand. And if this self-talk is not present – while performing automatized actions (driving, brewing coffee in the morning, brushing your teeth, etc.) – it will be soon.

Even though we are well aware of the amount of work we put our brains through during the day, we don’t realize how much the content of our thought process impacts our behavior. It changes our course of action and, necessarily, the consequences that follow. An example: two different individuals are frying eggs for breakfast. Both of them are cracking one of the eggs and suddenly the yolk breaks.

- Individual A: *inner monologue* dang it. What a way to start the day. This is bullsh*t.

- Individual B: *inner monologue* well…scrambled eggs it is.

Both have experienced the same situation but they reacted differently to it, resulting in different emotional states. We all have A days and B days but the relevance of all this is that cognitive appraisal of a situation affects emotional management.

But let us take a step back for a quick second. Where do these thoughts come from? Are they all automatic or do I get to control them? A little bit of both – as usual – but ultimately we get to create what we think. Once we realize we’re not enslaved by our automatic thoughts and that we get to mold them however we want, we become active agents in our emotional processing. I can put whatever I want into my thoughts: information, instructions, motivational quotes and so on.

What impact can self-talk have on sports performance?

Self-talk has been conceptualized as «a multidimensional phenomenon concerned with athletes’ verbalizations that are addressed to themselves» (Hardy, Hall & Hardy, 2005). They are mainly used to manage ones feelings, perceptions and cognitions while performing a certain task. Literature has suggested these verbalizations can enhance performance. The first studies – conducted during the late 80s – aimed to investigate the effects of self-talk on performance. Results determined that positive self-instruction could improve task performance in different sports (skiing, tennis or dart-throwing). One particular study proved that the use of specific verbal cues in elite 100-m sprinters allowed a significant reduction in times compared to baseline measures.

But not only has inner monologue proven its worth regarding performance; it’s also helpful in the learning process. Self-instruction verbal cues have been useful for athletes when learning new movements or in later stages of skill acquisition; it’s been proven in sports that require fine motor skills such as precision or hand-eye coordination (golf, basketball, etc.)

The matching hypothesis

There are two types of self-talk: instructional and motivational. The first kind, involves verbal cues that guide us through a certain process; the latter refers to inner speech that is meant to give us an extra push.

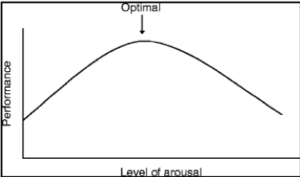

Which one is best? Science says that personal preferences are most effective. We can say em out loud or privately, use instructions or motivational phrases; and select our own cues or have them assigned to us. So it all depends. But it also changes according to the activity at hand. For example, throwing darts and long distance running are two very different tasks. They involve different muscular groups and pathways in our central nervous system. Consequently, they might call for specific verbal cues. Science suggests instructional self-talk could be more useful when performing a task that requires timing and precision – such as dart-throwing -. On the other hand, tasks that require pure grit and strength (long-distance running), could pair better with motivational inner speech.

This is called the «matching hypothesis» and it has been studied on long-distance runners. Results confirmed that motivational private speech helped reduce rate of perceived exertion (as would psychostimulants, aerobic training or a nutrition plan), resulting in an improvement in performance. So what this means is that (surprise, surprise) training our cognitive processing is just as effective as training the physical aspect.

What about negative self-talk?

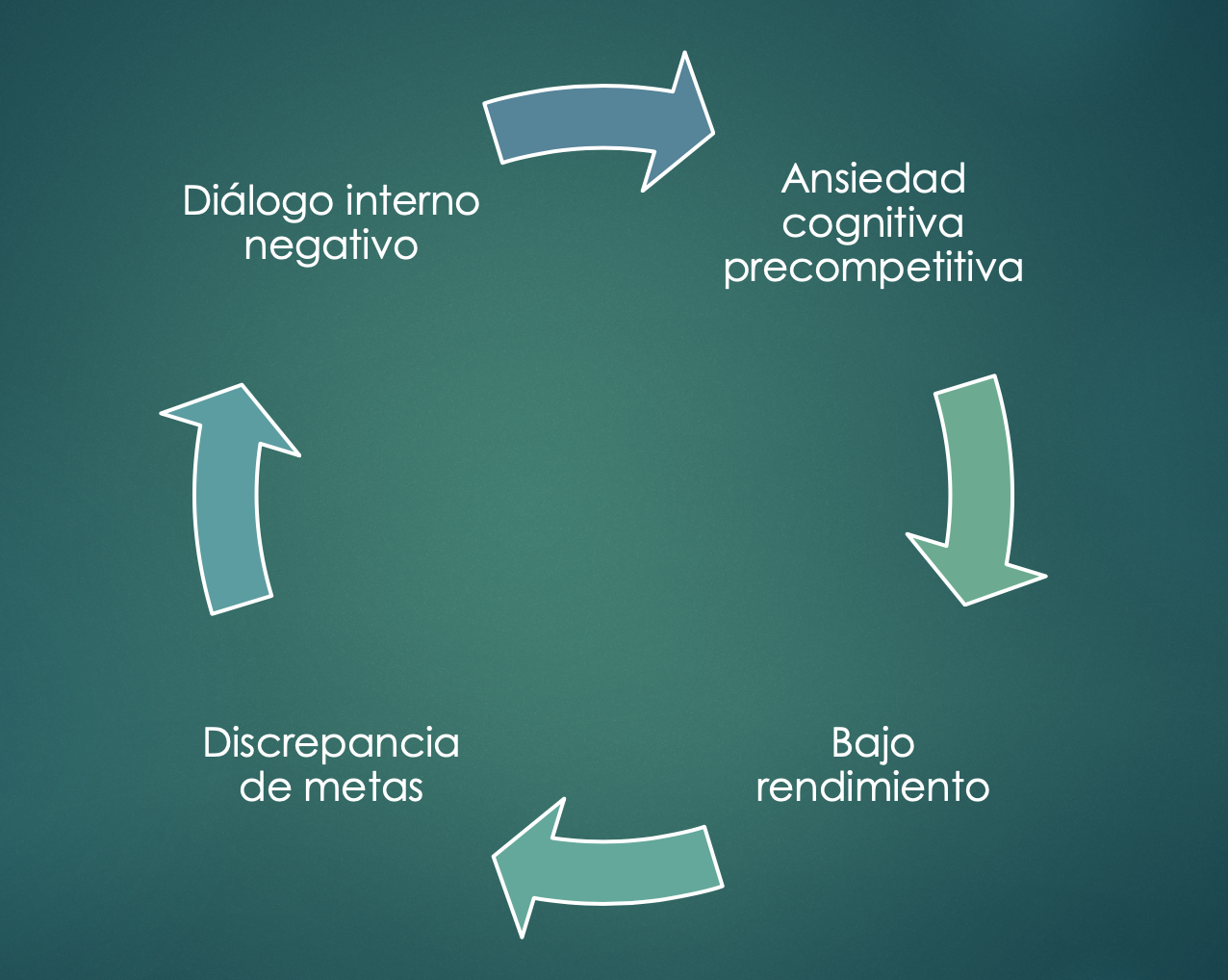

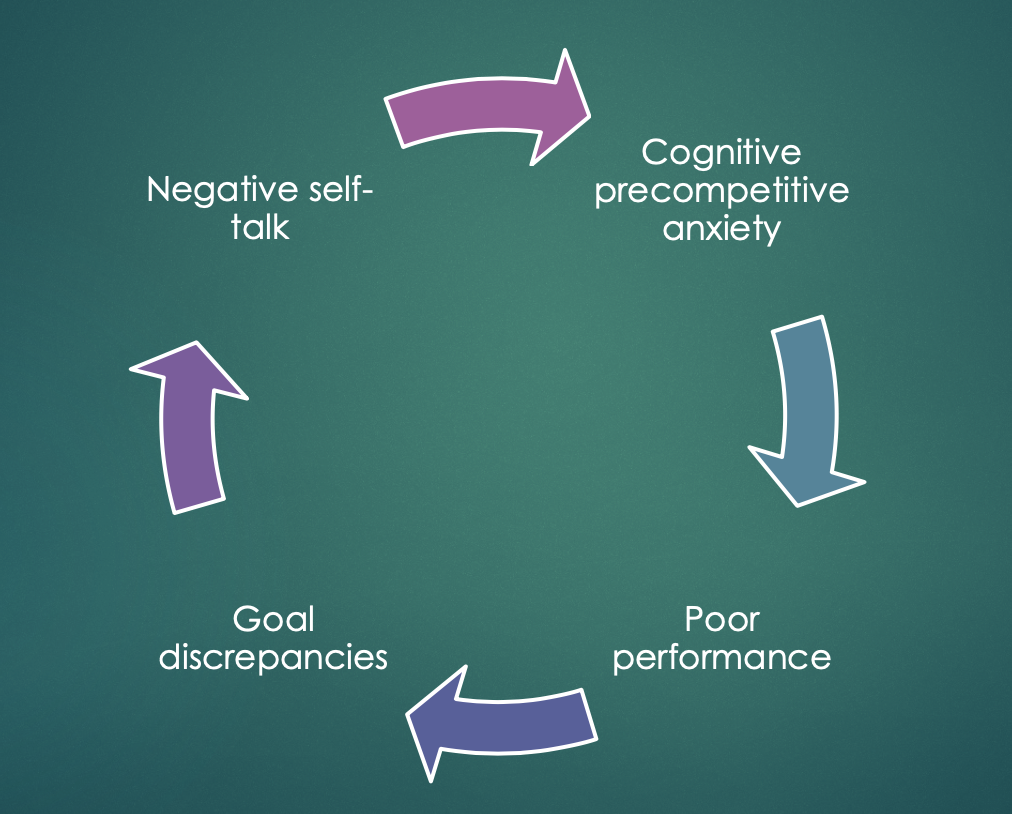

Carver & Scheier (1988) researched the effects of negative self-talk on sports performance and investigated its relationship with precompetitive anxiety and competition. They proposed a model which suggested that the athlete establishes goals and monitors their performance based on achievement. If the competition is not going well and the athlete detects this discrepancy between their goals and intended behavior, negative self-talk kicks in. In summary: the progress of competition influences the athletes’ thought content.

But we need to think of it as a cycle. Cognitive precompetitive anxiety – expressed in the form of worry and self-doubt – can predict poor performance; poor performance will necessarily lead to goal discrepancies and this perceived failure will provoke negative self-talk. This cycle sets the tone for future competitive events because it establishes a pattern in our cognitive processing. Unknowingly, the athlete has perpetuated a thought process that will hinder progress and performance in the future.

«Attention is a funnel for emotions» – Marta Redondo, PhD.

As we’ve seen so far, self-talk casts a large shadow when it comes to performance. We tend to forget the impact our thoughts have on our behavior, how they take hold of our attention and mediate our emotional responses. In college, a very special teacher once said that «attention is a funnel for emotions, an amplifier». If we focus on negative self-talk and our feelings of worry and self-doubt, our behavior will suffer the consequences and our performance won’t get any better. So, take matters into your own hands!

- If the workout includes a heavy front squat and you tend to lose tension under heavy loads, you might experience fear – trade that fear with self-instruction («high elbows», «chest up») or motivational self-talk («push through it»)

- If you’ve been practicing kipping pull-ups for the longest and you still don’t get the hang of it, this experience might lead you to doubt yourself – change that doubt with instructions («squeeze glutes», «pull down on the bar») or motivation («you got this»; «be patient»)

- If today’s class includes a 1RM Snatch, you’ve built up to your personal best but can’t seem to hit it after several attempts, don’t let negative self-talk get in the way. Find the problem and correct it. Is it the set-up? Or is it an early arm bend? Maybe all you need is belief. Talk yourself through it and give your attentional resources something productive to work with!

It’s all good and well to measure your daily food intake, run 800 m sprints on the track field and practice your snatch on a day to day basis; but, you should also spend some time training your self-talk. Choose the right verbal cues. Adapt your perception to the situation at hand and don’t ruminate on unforeseen circumstances in competition or in training. Motivate yourself when you need that extra push. Instruct yourself when you are not performing a movement correctly. If you do, you’ll manage your emotions more efficiently and, indirectly, you’ll maximize your performance.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1988). A control-process perspective on anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1, M-21

Blanchfield, A. W., Hardy, J., De Morree, H. M., Staiano, W., & Marcora, S. M. (2014). Talking yourself out of exhaustion: the effects of self-talk on endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 46(5), 998-1007.

Hardy, J. and Oliver, E.J. (2014) «Self-talk, positive thinking, and thought stopping», in Encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Hatzigeorgiadis, A., & Biddle, S. J. (2008). Negative self-talk during sport performance: relationships with pre-competition anxiety and goal-performance discrepancies. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31(3). Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Zourbanos, N., Galanis, E., & Theodorakis, Y. (2011). Self-talk and sports performance: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 348-356.